The Monthly Three - February 2023 Edition

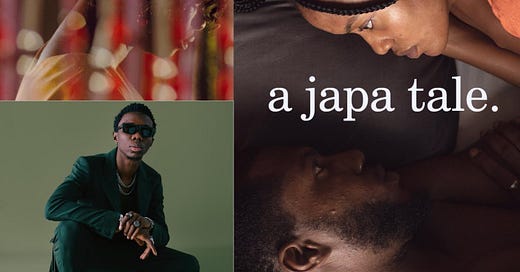

This month, I wrote about Eyimofe and A Japa Tale, two recent films depicting emigration; the political work that romance does in our intimate spaces; and some awesome new music.

Another month, another Three! It feels good to be updating the newsletter. Hope you guys are thriving in 2023. I’m done with the Masters, teaching for the first time, not reading enough, and getting ready to get even busier. Still, I missed writing these for you guys. It’s a great edition for this month of love. Shall we? Previous editions here and here.

Japa, Japa

My email signature for a long time has been a line on exile, “You will leave behind everything you love / most dearly, and this is the arrow / the bow of exile first lets fly.” It’s a line from a longer passage from Dante’s Paradiso 17:

You shall leave everything you love most dearly:

this is the arrow that the bow of exile

first lets fly. You are to know the bitter taste

of others’ bread, how salt it is, and know

how hard a path it is for one who goes

descending and ascending others’ stairs

In this passage, Dante captured beautifully this notion of the compulsion to leave one’s home, as well as the difficulty of both the path when people choose to walk it. That initial difficulty is sure, and it manifests itself differently from one person to another. There is currently a wave of upper/middle-class emigration of Nigerians – legal and otherwise, and I think portraits that depict non-physical costs of emigration are important in rendering human stories of our time as Nigerians. This is because if there is one thing that Nigerians often do, it is to underestimate all pain that is not physical, and overestimate our capacity for crude pragmatism when prioritizing the things that truly matter to us. Eyimofe and A Japa Tale (the latter is legally available on YouTube) are two films I’ve seen recently that center on the desire to japa, the Yoruba word we have given to the act of emigration from Nigeria for greener pastures. One thing that these films do well is to grapple with the moral, financial and emotional cost of our lives in Nigeria and the desire and decision to leave.

Eyimofe – meaning “this is what I want” or “this is my desire” in Yoruba – is about longing and failures to land. The film begins and ends with both protagonists in Lagos. One is Rosa, a hair stylist and a waitress, and the other is Mofe, a factory technician and security guard. The opening shot lingers on a jumble of wires, portending the messiness of the lives of the film’s two main protagonists, as they navigate their lack of means and how it dictates the lack of opportunity that will define their lives. Each of the chapters of the film are named Spain and Italy, both countries where the protagonists want to go, but have not and can’t. The film is a technical feat, thoughtfully done, gorgeously shot and ambles at a slow pace, perhaps too slow for those who are used to the easy glide of most Nollywood fare. It is a film with important things to say about who we are now, and what it means for how we live.

I came away really impressed with the quietly powerful performances in the film by Jude Akwudike who plays Mofe and Temi Ami-Williams who plays Rosa. Like many Nigerians, Mofe is stoic in the face of all that his life chips away from him: a sister and her children he is fond of that die suddenly, money he hoped to get suddenly taken from him, the pathway towards the foreign land he aspires to moving further and further away. When he explodes in anger at the factory where he works, we expect it, and are almost relieved for him, even though we know it endangers one of his jobs. His is a story so typically Nigerian, where the constant wave of private traumas and large-scale dysfunction often demand superhuman levels of resilience, and the only release we get from the pressure we face is each other.

Another thing that the film does quite well is that it speaks the language of delicate class interactions in Nigerian society fluently. Rosa’s story does this especially well. When we first meet her, she is standing with her face downcast behind a beaded curtain. She is a woman driven by her lack. Both of the men Rosa meets take the shape of something she wants, whether it is the money or the stability, and she is as uneasy in their company as she is desirous of their presence. We see how the weight of all that burdens her life denies her the ability to be the aloof, beautiful figure the expat would prefer that she were. Where she would rather hold herself apart from the lovesick landlord who clearly wants more from her than rent, she caves to his demands for more ease in her life. Her younger sister got pregnant, and their lack of options leads Rosa and her sister down the path to a human trafficker who forces them to make yet another compromise. In the end, she resigns to what she sees as her best option for a better life, the desire she has for herself will likely remain unfulfilled. From the film, we get the sense that poverty in Nigeria is expensive as hell, and can cost you everything from your dignity to your life without a moment’s notice.

The other film I saw was a short film called A Japa Tale, which told the story of a young couple where one of them is moving abroad. Dubem is a doctor, and Nigerian doctors and nurses are so poorly paid that they often leave the country in droves. The opening five minutes are a sweet, tender depiction of the love they have for each other. Dubem’s desire to emigrate is colored by his desire to remain with Emuche, who has just learned that she is pregnant. We learn that he has been keeping his japa plans from her until it was nearly time for him to leave, and her learning the extent to which he has gone far in his plans adds more conflict. His is not a story of a failure to launch, but rather a depiction of the cost his leaving will bear, for him and for her.

Another striking thing about A Japa Tale is how sparse it is, and how much the story does with little. It is short, told entirely indoors, in two or three rooms, and with a small cast of three. Because of its sparseness, the story has nowhere to hide. The dialogue had to be strong, the performances had to be good, and the editing had to be tight. In achieving all these things, this small film did a lot that many Nigerian films often struggle to achieve by keeping things simple. There’s a lesson to learn in that.

Music I liked

I’ve really enjoyed the success that new Cameroonian-American artist Libianca has seen with the success of her single “People”. The song is moody and reflective, capturing a mood of despondency and aloneness that a lot of us have felt before. I usually don’t pay these open verse challenges much attention, but it is notable to me that this is an artist who had not previously built a name for herself and the song is popular enough that she can do such a challenge. I can’t tell if this challenge was flagged off unintentionally because Buju (or Bnxn as he wants to known now) made a verse to it, but it’s still really cool. I love that people who are doing music in these parts have to rely less and less on club bangers to find audiences.

I really enjoyed Blaqbonez’ Young Preacher album. His flows were tight and melodic, and he largely keeps it simple. I enjoyed the great use of samples from older Nigerian songs in the production, like his use of Style Plus “Runaway” and Asa’s “360”, and some of the playful storytelling as in “She Like Igbo” and one of my favorites “I’ll Be Waiting” (I know the title is actually ‘I’d Be Waiting’ but ‘Will’ is more correct). Rap often does not do well in Nigeria, but I strongly believe that Nigerian rappers with an ear for melody, a skillfulness with local lingo, and unwilling to imitate style for style what rappers elsewhere are doing elsewhere would soar. Blaq proves it well, and I came away impressed with his style and approach.

That I even liked the album was a surprise for me, primarily because I didn’t bother with his previous and don’t care for the whole “fuck love” public image. I find it really childish and insecure, not to mention misogynistic, to insist that the only reason why someone would want to be with you, even if only sexually, is because of your money. Broke men find women to fuck them and marry them routinely. In the real world, people largely date and marry within their class bracket, and suffering women usually do not find anything other than equally suffering men. The whole thing is especially amusing because the first single from the new album is “Back in Uni” which talked about all the girls whose hearts he broke as a young student. Somehow, we are to square the notion that women only ever want money, but he had a whole harem of girlfriends he fucked around on as a student from a humble background. I rolled my eyes at the gleeful “omg all these girls I fucked around on”, especially as it was in the same body of work as songs like “Mazoe” and “Loyalty”. Perhaps that incoherence is realistic and typical, but I reserve the right to be annoyed by it.

Without much forewarning, Little Simz dropped a follow-up to the Mercury Prize-winning stunner that was “Sometimes I Might Be Introvert” . The fantastic new album “No Thank You” is less of a colorful smorgasbord than SIMBI. Instead of songs driven by lots of different influences from afrobeats to grime, we get a more spare offering with smooth, even-voiced flows over production reminiscent of 90s hip-hop designed for a laidback evening at home, or head-nodding on a long drive. “No Thank You” is an album I always play in its entirety, but my favorites are Angel, Gorilla, No Mercy, Heart on Fire, Sideways and Who Even Cares. In these songs, she covers various themes, like her experience in the music industry, the immigrant experience, mental health and love. From her previous album to this one, she imbues her music with an earnesty and thoughtfulness that adds wondrous complexity to her grit and braggadocio. Once more, she’s proved that she’s one of the best rappers you don’t listen to enough.

The Political Work of Romance

It’s the month of love, and I’ve been thinking about the work that romance does. I don’t just mean on the personal level of how it makes us feel, or even how much it is taken for granted that romantic love is something we desire. I mean ‘the work that romance does’ relative to the politics of gender in our intimate spaces, especially for women in heterosexual relationships. The ideal for marriage – that golden apex of human relations that we are all supposed to be striving for – is currently one that hinges on a romantic love. In the best of love stories, romance begins with the spark of a connection between two people that bears the promise of a great love. While the romance may flame out, it could as easily burn steadily over time in warming embers of companionship and comfort. Romance fulfils its promise for many people – lucky bastards, all – or at least seems to for enough people that it can make those of us who have not had our own great love stories feel inadequate for that fact.

While marriage was always understood as a beautiful possibility of human relations, it has not always been the ideal rationale for marriage. For much longer across many human societies, marriages were largely seen as economic decisions. I’m speaking in huge sweeps here, so bear with me, but I think this is largely true in a lot of places. Women were married off as girls so as to have long child-bearing years, ensuring that women bore as many children as possible. Families arranged marriages to consolidate economic prosperity and security, or to improve the standing of their families, or simply to ensure more hands to do agrarian work on which their local economies were built. While a marriage where one is treated with kindness was the ideal, being in passionate love with one’s partner was not deemed necessary.

Because the economic rationale for marriage was the default, and women’s respectability was hinged on being with a man in a way that the reverse is not true, it has often meant that women being treated with basic kindness was a fortunate thing. This is especially true in post-colonial societies where western, Judeo-Christian and Islamic perspectives of gender roles and relations were made to prevail. As the economic rationale for marriage continues to take shape over time due to women’s own growing economic power and the romantic rationale for lifelong partnership becomes more prominent, romance has become the factor on which women leverage in heterosexual intimate spaces in which they may lack other kinds of power.

Romance as an idea has endured because, in heterosexual intimate spaces, it creates a utopia where the socio-economic backdrop against which we live our lives doesn't matter. For men, romance dangles the allure of women who want to be with them for who they are, in spite of what they can do with them. For women, though, it does so much more. In romance, women are courted, their attention held, their hand sought. The men that pose as suitors treat them with care in order to have them close. Indeed, even with socioeconomic power fully asymmetric, romance represents the only arena in women’s relationships with men that men had to seek women. The world is full of contested space for women, but romance has always been a place where it has always been understood and uncontested that women had to be reached for, convinced, made to stay.

As women have fought and continue to fight for rights, access and space in their different political contexts, romance allows for the hope that you can get more of what you want from the man in your intimate space who has said that he cares for you. It is not for nothing that Delilah is one in a slew of historical seductress archetypes that have loomed large in many a cultural imagination. Delilah was able to wield power over Samson, so much so that she brought him to his knees. Depictions of women like her exist precisely because a woman’s power has historically been understood as a highly situational thing, circumscribed within the sociocultural remit of the men she is appealing to. Unlike a man’s power in his relationship with a woman in many places, supported tacitly and explicitly by the society in which he exists, a woman’s power has historically not been about what she deserves; it is what she can negotiate.

Romance does not erase the question of power in relationships, but it does complicate it and make that power harder to yield with the sole intent of control. We learn from bell hooks’ All About Love that power and control are incompatible with love, because the desire to dominate is ultimately driven by fear. From bell hooks’ All About Love:

“As a culture we are obsessed with the notion of safety. Yet we do not question why we live in states of extreme anxiety and dread. Fear is the primary force upholding systems of domination. It promotes the desire for separation, the desire not to be known. When we are taught that safety always lies in sameness, then difference, of any kind, will appear as a threat. When we choose to love we choose to move against fear - against alienation and separation. The choice to love is the choice to connect - to find ourselves in the other”

Romantic love as a driver for marriage, then, provides a lifeline of protection for women. The opportunity to have romance with a desired partner is the opportunity to have a connection, to find oneself in each other. It is a window through which women can negotiate safety and freedom within traditional institutions that society urges them all their lives to take part. If love has ever been there between a woman and her partner, then perhaps it can be called upon again to soften the asymmetry or create room for compromise where one’s needs and wants may clash with the other. The alchemy of romance, then, can create safety and softness out of nothing, but the sustainability of that safety and softness in our intimate spaces depends on harder, decidedly unsexy stuff like economic power and justice.

Now, those’s are flames that never die out.

And that’s all for my musings in this month of love. Until next time.