Welcome to another edition of your favorite newsletter! This month, it’s all film reviews. I tried to avoid spoilers with these, but nothing said here about the stories should stop you from watching these films. Get to it.

Don’t forget to share with all your friends. Previous editions here and here.

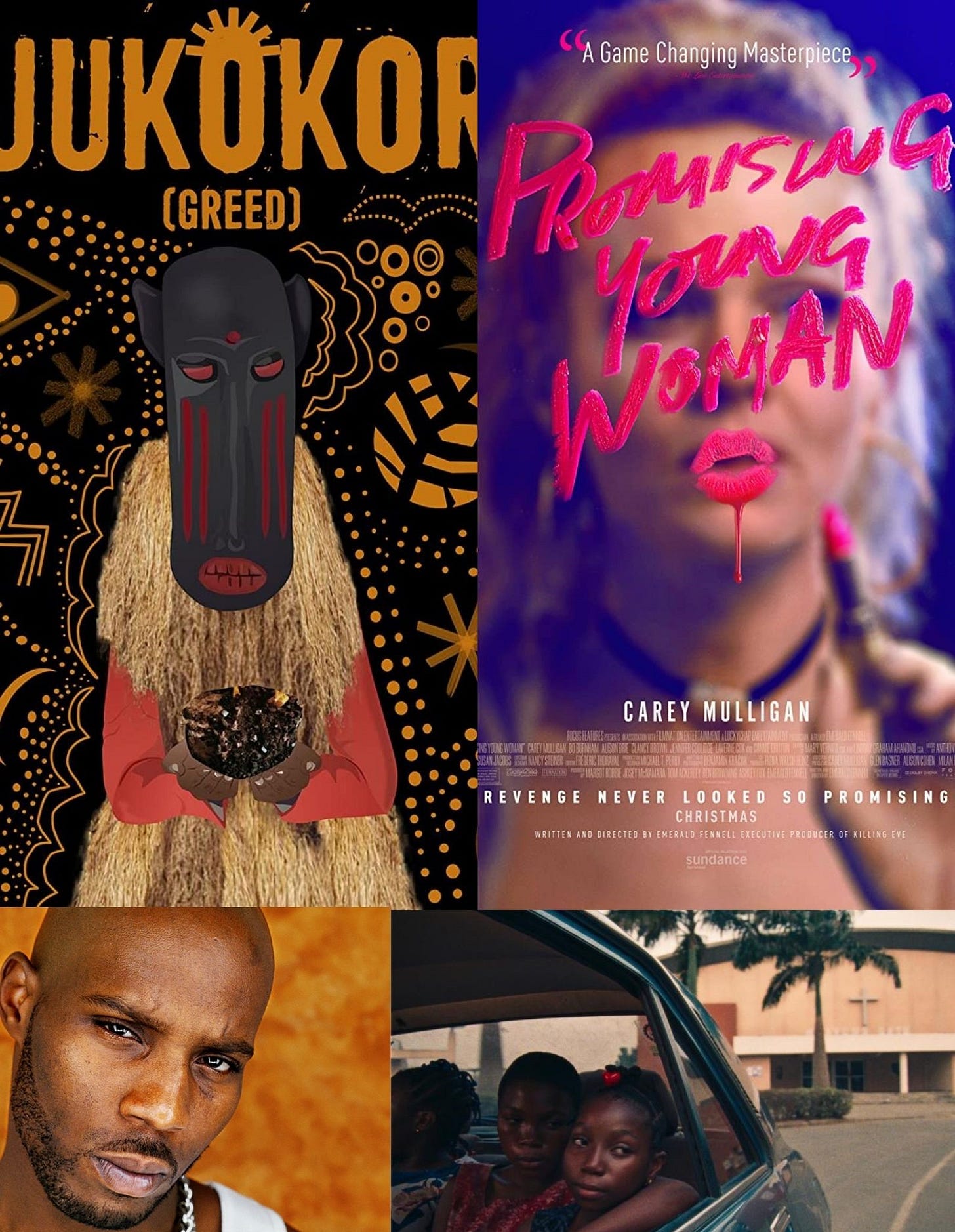

‘Promising Young Woman’ Pulls Its Punches

Promising Young Woman is a film that responds to the cultural moment by engaging with the issue of sexual violence and justice. When a young woman kills herself after she is raped by a group of guys at their medical school, her best friend Cassie Thomas (played amazingly by Carrie Mulligan) proceeds to get revenge against men who take awful advantage of drunk women.

Femininity is depicted in this film as a sheathed sword. I love the use of pastel colors and the poppy soundtrack in a film with such dark subject matter. This contrast was a statement in itself, about the way society sees women against how women sometimes see themselves and their experiences. Towards the end, they drag Britney Spears’ playful “Toxic” through the mud and make it gritty and haunting in a way you would never have imagined. It kinda reminded me of what Jordan Peele did with “I Got Five on It” in his horror film Us. In fact, Cassie’s final act where she shows up at a bachelor’s party dressed in a sexy nurse costume acts the same way the music and all the colors do; seemingly harmless, but with steely focus.

Promising reminds me a bit of Steve McQueen’s Widows, in the sense that it is not quite what it is advertised to be. Widows was presented as thriller where a group of wives of drug dealers have to pull off a heist to pay off their dead husbands’ debts, but it ended up being a much quieter film than the Oceans-like synopsis suggests. Similarly, Promising was sold as a “rape revenge” film, but it’s really a critique of revenge as a tactic. Cassie’s life stagnated after the death of her friend; she quit graduate school, has no friends, no love life, and works at a cafe and her boss is the only person we see her talk to until she meets and falls for her former classmate Ryan Cooper. After she brings her brief love interest home to meet her parents, her father says to her, “we missed Nina, but we really missed you.” After her parents subtle ‘get out of this house now’ present of a suitcase, her boss asks her why doesn’t she move out, Cassie simply says “because I don’t want to.” Her thirst for revenge, therefore, is cast as a sort of death, the lack of willingness to move forward and actually have a life. This is more what the film is about; indeed, a real “rape revenge” film will lean into its premise by showing us the satisfaction and catharsis, even if she comes up empty afterwards and is left with as much pain as when she started.

Instead, because of its anti-revenge stance, the film denies us of the full weight of the character’s anger. The opening scene was and all the other scenes where the men were willing to take advantage are uncomfortable as hell, and it was pretty sickening to see the men willing to take advantage of her when she pretended to be drunk be freaked out when it turned out she was not. You get the sense that whatever violence she metes out to these men is immensely justified, but that is pretty much where it ends. We don’t, for example, see what she does to her -- I’m not even sure if this is the right word -- victims. It’s implied that she gets them killed, but even that isn’t entirely clear. We have to assume that the rough-looking guys she meets after she’s done with her “victims” are there to finish the job, but we can’t say for sure. When Cassie meets up with Madison, a woman she was friends with in med school, she gets Madison drunk and arranges for her to accosted by some guy to drive home a point to Madison about her callousness regarding what happened to her friend. Madison then called Cassie and asked what happened, because she was too drunk to remember. Cassie told her that he just took her to a room and tucked her in so she could sleep. While she could have been lying, we can’t say we know for sure. We assume she got some of the men killed, but she certainly did not kill everybody. I wish the film did not avert its gaze.

What we do get, and in full detail, is her death. We get the full view of Al, the guy who as a student in med school violated her friend, strangling her to death; it was the grimmest depiction yet in the film of how far a “nice guy” would go to avoid accountability. We get the man that had said he loved her do anything to make it go away. We would see Al’s best friend basically absolve him of all wrongdoing, even without knowing what he did and why, and giving him an out. We get uncomfortable conversations with the female dean who handled her dead best friend’s case apply a sense of justice and sympathy concerning sexual violence when it suited them. It’s not unlike what we know of how society often shields male abusers of all responsibility and uses respectability (why did she drink that much? What did she wear?) to measure the extent to which women can be sympathised with.

I have no idea what moving forward with one’s life that has been rocked by violence should necessarily look like, or if there is even a right way to do it. It feels strange that the seeing the same authorities that failed Nina rode in at the final minute to offer justice for the wrong done be the ‘happy ending’, especially given that people who have abused women often walk away with a slap on the wrist. Cassie’s quest for revenge was also rebuke of the authorities that failed her friend. I get not believing in revenge, but the filmmaker does nothing to challenge our imaginations on what justice actually looks like.

‘Promising Young Woman’, Related

Still Processing is one of my favorite podcasts, and I really enjoyed their conversation on Promising Young Woman. Check it out here, I especially liked that they held the film in conversation with I May Destroy You, which also engages with how survivors of violence seek justice.

I also liked the engagement with whether Cassie did go on a suicide mission in the ending. I think she did, but this review engages beautifully with the question. Like Still Processing, it also engages with the I May Destroy You as well, given that the film was meant to have been released closed to when that mini-series dropped. I personally don’t think either the show or the film gives a satisfying ending, or even a particularly restorative one for its main characters.

‘Ojukokoro’ Holds Up a Mirror

Ojukokoro begins with an unflushed, shit-filled toilet and the flies that surround it. This pretty much sets the tone for the rest of the film; it does not flinch or avert its eyes away from the darkest side of Nigerian society’s underbelly.

The amorality of Nigerian society is the main character in Ojukokoro, but its social awareness is not the point. In the film, a manager whose name we never learn of a shady as fuck petrol station is plotting to rob his place of work. This “petrol station” is really a front for a drug and money laundering scheme. While this is happening, his friend Jubril has just had his wife kidnapped by political rivals, and Monday, a gambling addict who works at the petrol station, also planned to steal from the station to settle a debt. The film is full of strivers of all stripes: politicians, lower-income Nigerians, gangsters. The un-remarkableness of the names of their characters made the film feel almost like the names were not the point, that this was more of a societal observation about Nigeria than about this particular film itself. These people would do anything for the money, including kidnap and kill for it. Some people would do these things just for the sake of having money, others will do it for the sake of power, and still others would do it because they have problems only money can fix.

There is no desire to depict Lagos in the best light. Ojukokoro was mercifully devoid of any images of the Lekki-Ikoyi bridge, and wealth in Nigeria is depicted as it often is; of dubious origin, with hustlers scrambling to get in on it edgewise. Also unlike a lot of other films, the pidgin and the Yoruba flowed naturally, and the use of language -- Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, Pidgin and English -- all felt familiar in how they danced together in everyday speech.

Some things did not feel tight enough for me -- why did Jubril give him a gun, of all things, for his birthday? Why did the lead character not ask his friend for 15 million he needed? Why did the recurring motif of the masquerade recur for a minor character, as opposed to the lead? -- but they did not take away from my enjoyment of the ride.

While the story worked well, it did make me think of what I’m beginning to see as a sort of Nigerian-specific test, similar to what the Bechdel Test does for engaging with how women are depicted on screen in American television and film (sidebar: I think the Bechdel Test is useful for engaging with Nigerian film, too). The question this test will pose is simple: in a conversation between two lower-income people, are they talking about something other than money?

I understand that Nigerians are strivers and aspiration is a major thing for us, but whether people are wealthy or not, we live full lives; we have good and bad relationships, family that stresses us, commutes that annoy us, exes that leave us weak in the knees, partners and kids that we care about. Even the lighthearted films about marriage and the like all depict a wealthier reality than most Nigerians have. The films, then, kind of operate in the way hiphop does for many of its listeners; as a vehicle for escapism, a space to engage with a reality you don’t necessarily share, but speaks to something you find desirable. For example, hip-hop gives us the hyper-masculine guy with lots of money and women, or the Bad Bitch with lots of her own money that all the men want to sleep with. I think our stories can serve other purposes. Lower-income people also have weddings that break their own albeit-smaller bank accounts, or get their hearts smashed to a million pieces. Why do we not see those stories? I wonder if this is one way that the increasing difficulty of social mobility in Nigeria manifests.

‘Lizard’ Kills It

I should name my biases clearly here. Lizard was written by the brothers Akinola and Wale Davies, the latter of whom is one half of Show Dem Camp, whose music I love. That said, I liked this Sundance and BAFTA-winning film a lot for its quietness and subtlety. The opening scene in Lizard sees armed robbers preparing for an attack on the church, and we see one of them lingering behind as he holds a baby. Just that quiet characterisation told us enough about the character to make what he does later in the film believable. It’s the kind of economy I wish more Nigerian filmmakers had in their storytelling. I also really liked the little girl who was the lead character and how, having seen some of her church’s dirty laundry, felt nothing about using church money to buy a snack. That scene made it all feel like a short coming-of-age story in a way. Anyway, definitely worth a watch.

Lizard is available for a brief time here on the BAFTA Shorts Youtube playlist, along with all the other short films nominated for the award. Make your way through them, even though you might need a VPN to do so if you’re not in the UK or the US to see some of them.

Rest in Peace, DMX

Growing up, I was frankly afraid of DMX. Everything about him scared me then; the rapid-fire bark of his voice, the lack of adornment of his anger, his unapologetic rawness. He seemed to have no use for sleight of hand. Everything he sang about felt true in a way that it did not when other rappers made music about the same realities. To have landed like an anvil onto our consciousness at a time when people like Jay-Z were coming into their own was an accomplishment in itself, but there truly has been no one like him since.

It took me until my 20s to see beyond the dark, and listen. It took age to understand that he spoke of the world he knew, and to see the way he triumphed and reached out for light through his music. I’ve been listening again, not just to the anthemic “Ruff Ryders Anthem” or “What’s My Name”, but to the prayers he includes in all his albums. I’m making my way through his albums for the first time in a long time, and in awe of how he was able to channel his rage, his conflict, and his fears through his music. Anyone who has ever been rendered incoherent in anger knows how much it requires to speak audibly and clearly when troubled and seeking. So go back and listen to X. I wish he had stayed with us longer, but at least he is at peace. I can live with that.

Until next time.