The Three: #EndSARS Edition

#EndSARS #EndSARS #EndSARS #EndSARS

Apologies for what is a lengthier intro than normal.

The surfacing of a recorded killing of a young man in Ughelli, Delta State, on October 9 sparked protests against police brutality across Nigeria. The focus of these protests is a unit of police called the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), which is notorious for their extra-judicial killings, kidnapping, extortion, and torture of ordinary Nigerians. If you’re a Nigerian, especially from the southern part of the country, you either have a SARS story or know someone who does. SARS brutality has been a subject of conversation and advocacy for years, and the Nigerian government has announced the disbandment of the unit in 2017, 2018, and 2019 only for it to resurface once more. The Nigerian government announced a disbandment of SARS yet again last week in response to the protests, but understandably nobody believes them this time. What we want now is for murderous police officers to be arrested and charged, and a system through which families across the country can get justice. Here are some useful backgrounders here and here.

I had initially decided not to write anything about the #EndSARS protests now, mostly because I’ve been too busy experiencing what looks to be the biggest nationwide protests we have ever had in a long time. I have been to some protests myself, donated, and talked among friends about their own experiences of the movement, all in an effort to form some kind of understanding of what it all looks like beyond my eyes. I may have a blog, but I do pride myself on knowing when to shut up and listen. In fact, I had a whole other edition planned for October, and perhaps that might have to come out in November or later, depending on how things go. I obviously decided to go ahead and write something about the current movement, and it is so I can hopefully achieve what writing always does for me: provide a sort of shelf for my thoughts, imposing upon them a certain order and light that helps them right themselves. As always, I hope that by sharing the way I’m thinking about the movement so far I am also encouraging others to find useful frames for thinking about what is happening in Nigeria.

I cannot write all of this without a shout-out to Nigerian youth-led media houses likes Stears Business, Zikoko, Native and The Republic Journal for their incredible work in this time. They are part of the “adhocracy” that Nigerians are creating (more on that below), because the established local media is among the many institutions which has failed us. It is true, even if the reasons for that are too numerous and complex to get into right now.

All of that said, here are my somewhat disjointed thoughts on the current moment, highly subject to change. Previous (happier) editions here and here.

A Nigerian “Adhocracy”

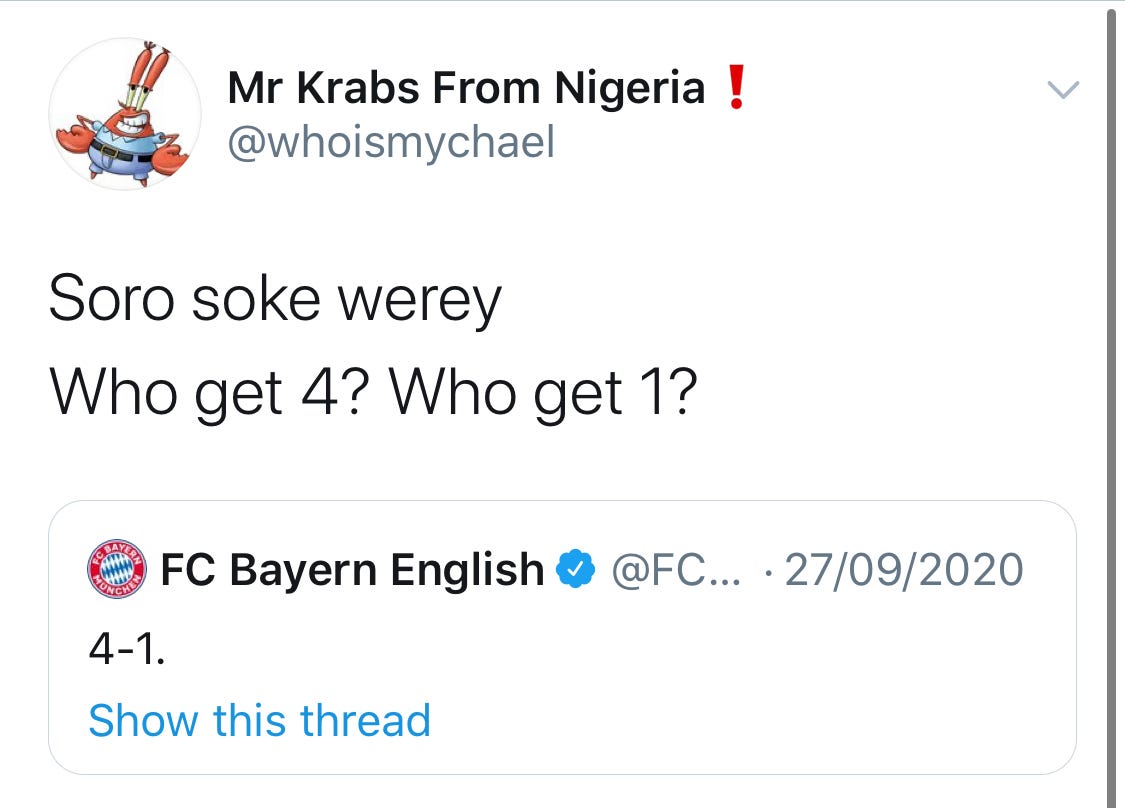

Things that are resonant in this protest movement are either created for the moment, or re-contextualized to the moment. What is now becoming a catch phrase “soro soke (speak up)!” was not originally come up with for any kind of revolution, as you can see from the originating tweet below. “Werey dey disguise” (harder to translate) started as a joke. Even Davido’s song “Fem” with the line “I dey live my life/man dem turn am to shoot on sight” was actually a diss track on Burna Boy and a reply to his song “Way Too Big” on the latter’s “Twice as Tall” album. The “Buhari has been a bad boy” line, though, was directly from this moment and made its way from a viral HipTV interview to protest chants across the country.

But slogans aren’t the only thing being repurposed. The social media networks that were being used to do decidedly unpolitical things like dating and discussing everything from football to music are being used to create and share video content and messaging. The social media-driven protests last year where women mobilized against gender-based violence from police seemed to have been good practice in this kind of repurposing, as many young Nigerian women have used those same networks they used to raise awareness of issues they face to mobilize funding, legal aid, medical care and even security for the recent #EndSars protests. This year, Nigerian women also mobilized to fund legal aid and other support for a young woman named Seyitan who had accused popular Nigerian artist D’Banj of rape, so we have been primed for a fight for almost two years straight now. It is not lost on me that the enormity of the goodwill that these women who are contributing massively to #EndSARS was absent when they were fighting for women’s rights specifically, and that they certainly would not have gotten it for a movement focused on issues facing women alone. We’ll have that conversation another time.

The repurposing we see of existing social media networks from more playful matters to those of national importance is a feature of recent youth-led movements, not a bug. In Sudan, women’s facebook groups that had hitherto not been at all political were suddenly mobilized for the explicitly political means of fighting oppression. This is after the famously Facebook-led Arab Spring protests in Egypt and their use of digital space for in-person movement that would eventually topple their government. Much like what we’re seeing on the ground in cities across Nigeria, the 2013 Gezi Park Protests in Turkey also used social media to mobilize logistics in a peer-to-peer fashion, everything from food and medicine to legal aid and security. All of these citizen-led social media-enabled protests -- from Sudan to Turkey to Egypt -- saw significant police responses in the form of water cannons and violence. Even protest tactics like alternating between large concentrated rallies in few locations and smaller clusters in multiple location is a page out of the Hong Kong protesters’ playbook.

As Zeynep Tufekci notes in her 2017 book Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protests of these other movements, and is also true of these #EndSars protest, the logistics on which these long-term protest movements live and die are often not created by organizations that had existed before, but rather “organizations that evolved during the protests, or by unaffiliated individuals who had simply shown up.” This “adhocracy” as Tufekci calls it, that we have seen emerge from the #EndSars protests has featured such things as: having dedicated people picking up trash on protest grounds; church and jumaat services on protest grounds; decentralized food distribution; fundraising to pay for protests themselves, as well as for surgeries where insurance companies fail and to compensate some victims’ families.

This sense of shared responsibility where protesters have to take care of themselves and those around them adds a sense of community unlike anything I have seen as a Nigerian. In the Abuja protests I’ve gone to, there is care and support and looking out for the person next to you. There are severe warnings before you march that any man who sexually or otherwise harasses a woman during the protests will get a beating (this has actually been acted on in Lagos). There is food and water donated by fellow protesters. All of this, against the backdrop of danger, state-sponsored violence, and possible disruption from hired thugs.

The development of these “adhocracies” are, more than anything else, an act of moral imagination that is a daily rebuke of the discrepancy between the way a people see themselves and the way a government sees them. Nigerians know their society as a low-trust one where access to public services is often a question of access to patronage networks, and young Nigerians have only ever known a government that will do nothing to help them, or sees them as lazy and an inconvenience. Moe Odele is a young woman who -- along with a young man named Adetola -- set up a legal aid structure where over 600 lawyers from across the country are providing pro bono legal support to illegally imprisoned protesters. She shared her frustration at the sluggishness of existing systems meant to provide legal aid.

Watching the way we take care of ourselves on protest grounds has been the most emotional thing for me the few times I’ve partaken in these protests myself. For all the explicitness of the message we bring and the massiveness of our numbers, the most powerful thing has been watching us assert over and over again that our lives do indeed matter. We do that in candlelight services honoring the dead and speaking their names, and we do that every day by taking care of each other in a way that our government never has.

Beware Thy Advocates

Early on in the protests, Burna Boy was roundly mocked by a lot of people in the first round of protests for his past criticisms of Nigerian young people and not being around for protests (he explained why later on). I’ve written about what I think about his more politically conscious mien before, so I won’t get into it, but it certainly got to the point where protesters did not want his music played during the lighter moments of the protests. Davido’s song “Fem”, which was a diss track aimed at Burna Boy, is pretty much the unofficial anthem of the protests.

Davido got a fair bit of goodwill early on, but we got our reminder not to lionize any celebrities too much. When he visited the Inspector General of Police last week, video footage showed him quick to deny playing any part in the protests. This, even though his comments until that moment (and since) had been on the side of #EndSARS protests.

I had a knowing smile as I watched the video, because it reinforced something I think is one of the more insidious aspects of decades of bad leadership. Nigeria has been dysfunctional for so long that we easily forget that policy advocacy is actually a learned skill. This is a country where people mostly rise to power unprepared for the elected offices they would hold, so it is easy to forget that governance and the managing a sprawling bureaucracy is also a skill. Davido was not sent by any protesters to speak for them, and he should not have taken that assignment up on himself. Most people have never actually been in a closed-door meeting with people with power before, and are likely to get as intimidated as Davido was, and buckle. Even when they’re able to get the words out, it still takes a trained eye to know when you are being taken for a ride, as was the case when Davido was told to head up a panel to oversee the evaluation of SARS officers. Besides, the IGP and the entire government he seeks to protect are political actors who have lied many times before. This kind of thing where passionate famous people coast on celebrity status alone into arenas where they really should not play in is how misguided populism takes hold, thereby further entrenching the inefficiencies and incompetences than we are looking to change. The spotlight can be seductive, and any degree of self-awareness would have led Davido to understand that he was being given a task that he in no way had to the technical skills to carry out. Even just a little less naivete would have allowed Davido to see that the offer being made to him was a polite way of making him go away, something Yorubas would call “gba, je’n sinmi (take, let me rest).”

The way the “adhocracy” thrives is by letting people who have the networks and knowhow to provide certain services they are capable of providing to sustain the protests. It is just as important that people sympathetic to the movement who have a more in-depth understanding of public policy and how governance actually works bring that knowledge to bear and help develop policy that help achieve what protesters would like to achieve. Many people don’t want to hear this, but there is really no getting around engagements on the policy side. That is why I really like the way Falz has engaged, bringing to bear his knowledge as a trained lawyer and sharing information on the processes governing the National Human Rights Council (less so on the state-level investigative panels, that I’m pretty unconvinced by because of what seems to be Federal level discretion to act on their recommendations).

This movement is so far a leaderless one, and much the same way people have stepped up to create an infrastructure for the sustainability of the protests, people will have to do the same to get the policy recommendations developed in a way that government can act on. It is true, though, that a lot of the people who will emerge to drive these policy conversations will be doing so for their own political ends; there is also no getting around that. The silver lining here is that these people will have to take it upon themselves, and will likely own whatever successes they come away with, just the way they would the failures.

A Note on Respectability

A rare moment of good news this past couple weeks is that the good people at the payment company Paystack just got bought over for hundreds of millions of dollars by the American payments company Stripe. The reaction to the news, though, typified everything that has always rankled about the way we talk about who does and does not deserve to be attacked for who they are.

One half of the resoundingly successful Paystack team Ezra Olubi has long locs and sometimes wears makeup, and the commentary was about how SARS’ targeting of people who look like him would have meant judgement of him based on what he looked like, rather than who he is and what he can do. The trouble with this is that even if Olubi was indeed a good-for-nothing young person who only knew how to lie around in a indica-induced haze all day, he still would not deserve to be killed. We do not need to be exceptional or “responsible” to deserve respect.

At some point, we would need to reckon with the fact that the notions of respectability that we have accepted from our parents’ generation do more harm than good. It is why, in the heat of the anti-AEPB protests, many people justified the cruelty and sexual violence women who were caught in police raids were met with because they were allegedly sex workers. To this day, many young Nigerians still do not understand the connection between accepting respectability in one context but not the other. Whatever you might think of a person’s choices of what to do with their bodies, they’re just as human as you are. And they don’t need to be a founder in the next multimillion dollar startup exit for that to be true.

We Jammin’

I can’t leave you without a little somethin’ to step to, can I?

I had a whole ass review for Tems’ new EP planned before I got on my aluta shit. No vex. Next month ehn? But for now, go check the EP out. The summary of my thoughts on the EP is that I like it, and I think the emergence of artists like her augurs well for the industry as a whole. A mere five years ago, she would most certainly not be within striking distance of mainstream Naija pop music.

In my review of Adekunle Gold’s new album last month, I talked about his growth and how it makes me really expectant of Simi’s new album. I’m glad to say I was correct; Simi’s very solidly in her grown and sexy mode for her latest EP. Every single song on Restless II makes me smile. Get to it.

It is also worth noting that music has been a big part of this movement, as it typically is wherever young people are gathered. Zikoko has a nice piece on that as well. They also put together a list of some of the best protest anthems from Naija music, even though I think a few faves are missing.

Dua Lipa and Jessie Ware both gave us solid albums that made us wish we were in Studio 54 circa 1970, so Roisin Murphy choosing 2020 as the year to finally bless us with Roisin Machine is icing on the dancey, glittery disco ball cake. I’ve loved her since Moloko first dropped Sing it Back, well into Ramalama, even that weird and wonderful collaboration with Handsome Boy Modelling School Truth Hurts. She’s the truth. And I’m so pleased that she’s still who she is. As she says in her recent NYT interview, she has “come from club culture, but [has] also come at it.” My favorite thing -- and something I think Dua Lipa did not quite manage -- is how she manages mood. Dance is meant to be sexy and sweaty and euphoric, but it can also be ponderous and moody. This new album does all of these things well.

If dance is not really your thing and you’d rather chill with something less uptempo, check out Norah Jones Live at Home series. She performs some of her newer work, but also gives you a super stripped-down version of her classics as well. The New Yorker calls these little live sets “extraordinary”.

Until next time.